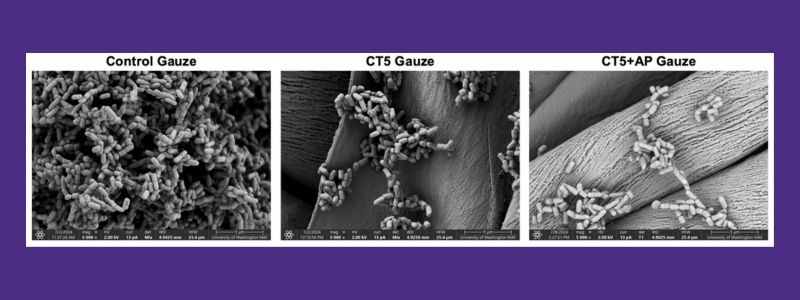

Scanning electron microscopy images of the bacterial biofilms on untreated cotton gauze (left), gauze with layer-by-layer coatings of chitosan and alginate (CT5, middle), and with further addition of alpha-sheet peptide (CT5+AP gauze, right). There is over a 600-fold decrease in the bacterial biofilms with the alpha-sheet peptide-treated gauze.

When skin is damaged by a wound, the body responds by forming a protective barrier to prevent infection. While some bacteria naturally live on the skin without causing harm, a skin injury creates a warm, moist, and nutrient-rich environment that allows bacteria to thrive and form communities called biofilms.

Biofilms are clusters of bacteria that attach to surfaces—such as wounds and medical dressings—and produce a protective layer containing amyloid fibrils. This layer shields bacteria from antibiotics and the immune system, making infections harder to treat. Biofilms can form within just 24 hours, leading to prolonged healing, more expensive treatments, and an increased risk of serious complications. Current treatments, including antibiotics, are often ineffective in fully eliminating biofilms, contributing to the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

Wound infections in injured or surgical patients are a major health concern. They can prolong hospital stays, increase medical costs and often require painful procedures to remove infected tissue. In severe cases, they can even raise the risk of death following an injury or surgery. Additionally, many wounds are infected with multiple types of bacteria, making treatment more difficult. Some antibiotics only work against specific strains, and certain bacteria—such as E. coli and Staphylococcus aureus (Staph)—have developed antibiotic resistance, further complicating treatment.

A new approach to biofilm prevention

Researchers led by UW Bioengineering Professor Valerie Daggett previously discovered that as amyloid fibrils form within biofilms, they pass through an intermediate stage called an alpha-sheet (a-sheet) peptide structure. This structure plays a key role in making infections more difficult to treat. By preventing amyloids from forming, these peptides help break up biofilms and return bacteria to their free-floating state. This makes the bacteria more susceptible to antibiotics without directly killing them, reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance. In a study published in the Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, Daggett and her team used computational design to create synthetic peptides (small protein-like molecules) that mimic a-sheets and can block amyloid fibril formation. Her lab partnered with Professor James Bryers’ lab which carried out the studies to develop the bacterial biofilm, anti-infective gauze and the antibiotic incorporation.

Engineering a smart antibacterial gauze

To deliver these peptides effectively, the research team designed a specialized gauze using a technique called layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly. This process involves coating gauze with alternating layers of two natural antibacterial materials—alginate (from seaweed) and chitosan (from shellfish). These layers control the release of peptides over time, ensuring a steady dose reaches the wound.

When tested, the functionalized gauze successfully released peptides for 72 hours, was safe for human cells and significantly reduced biofilm formation—even in antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Next steps toward clinical use

The researchers plan to further evaluate the gauze in lab models that simulate bacterial growth and conduct additional studies to confirm its safety for human cells and tissues. They are also seeking funding to test the gauze as a wound dressing in rodent models. Another key step will be assessing the gauze’s long-term stability to ensure it can be stored for extended periods, as required for commercial bandages.

Daggett and her team have extensively studied amyloid-forming proteins and their role in diseases such as Alzheimer’s and diabetes. Learn more about their work developing diagnostic and therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s and uncovering the connection between Alzheimer’s disease and Type 2 diabetes.