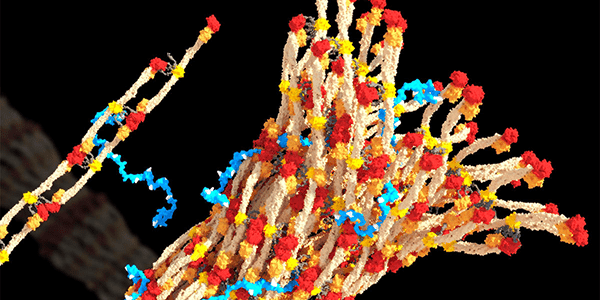

Image: A 3-D rendering of fibrin forming a blood clot, with PolySTAT (in blue) binding strands together.William Walker/University of Washington

UW bioengineers from Robert F. Rushmer Professor of Bioengineering Suzie Pun’s lab, along with collaborators from Emergency Medicine and Chemical Engineering, have developed an injectable polymer that could keep soldiers and trauma patients from bleeding to death. The researchers published their findings in the March 4 issue of Science Translational Medicine, and their work was featured on the issue’s cover.

Bleeding is responsible for 30 to 40 percent of trauma-related deaths and is a leading cause of death in the initial hours after injury. In some cases of bleeding there’s not much first responders can do, particularly in combat environments and other low-resource settings blood product treatments aren’t always available.

The UW researchers’ polymer, PolySTAT, addresses the need for a stable, reliable treatment that can be used on the field. When injected, the polymer seeks out unseen or internal injuries and starts working quickly.

The researchers were inspired by Factor XIII, a natural protein that helps strengthen blood clots. After an injury, a clot forms when blood platelets gather at a wound, which is then reinforced by specialized fibers called fibrin. Both PolySTAT and Factor XIII work by binding fibrin strands together and adding “cross-links” that reinforce clots.

However, the researchers found that PolySTAT formed much more stable clots. They examined PolySTAT in an animal model of typically fatal femoral artery injury in rats. “We were really testing how robust the clots were that formed,” said BioE Ph.D. student and the paper’s lead author, Leslie Chan. “The animals injected with PolySTAT bled much less, and 100 percent of them lived.”

PolySTAT potentially offers several advantages over blood products. Blood products are expensive, need to be kept refrigerated or frozen, are susceptible to bacteria and can carry infectious diseases. They also may not work well in a patient suffering a traumatic injury, who will start to lose a protein that helps fibrin form. PolySTAT doesn’t require special storage and can strengthen clots even when a patient’s levels of fibrin precursor are low. “This is something you could potentially put in a syringe inside a backpack and give right away to reduce blood loss and keep people alive long enough to make it to medical care,” said Dr. Nathan White, co-author and assistant professor of emergency medicine at UW.

The researchers said that PolySTAT’s initial safety profile appears promising. Their next steps are to test it on larger animals and investigate whether it binds to unintended substances. They also will look into its potential as a hemophilia treatment, and for integration into bandages. If these studies go well, PolySTAT may enter human trials in five years.