UW Bioengineering Ph.D. student Renuka Ramanathan led a team of researchers from UW Bioengineering Assistant Professor Kim Woodrow’s lab that recently received first place at the recent UW Medicine Inventor of the Year Award Ceremony and Science Technology Showcase, hosted by UW’s Science & Engineering Business Association (SEBA) and the Buerk Center for Entrepreneurship.

The Inventor of the Year Award Ceremony, held November 6, 2014 to recognize UW Medicine Lifetime Innovator Buddy Ratner, hosted an innovator showcase that presented exciting biomedical research underway at UW. At the Science and Technology Showcase (STS), held on January 15, 2015, participants explored the commercialization potential of their research. They pitched their projects to an audience of fellow scientists and engineers, MBA students and a judging panel, which included local entrepreneurs and investors

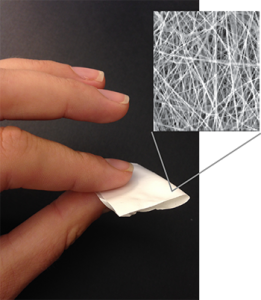

Empreva is a fiber-based drug delivery technology for HIV prevention and contraception.

The team, which also includes BioE Ph.D. student Anna Blakney and research scientist Yonghou Jiang, pitched Empreva, a discreet drug delivery technology that offers women an innovative way to protect themselves against HIV and pregnancy. Empreva is a rapidly dissolving fabric that releases potent doses of antiretroviral and contraceptive drugs upon placement in the vagina. Its quick action allows its on-demand use, either before or after sex, and its local action may limit negative side effects.

HIV disproportionately affects women, who also bear the dual burden of protecting themselves from unintended pregnancy. Young women are particularly at risk; HIV infects two times as many woman aged 15-24 as men. Additionally, half of all pregnancies in high-burden HIV areas such as sub-Saharan Africa are unintended. Empreva is well suited for the developing world when compared to other HIV prevention strategies like oral antiretroviral drugs or condom use, due to its dual purpose and low cost.

No product currently on the market allows women to initiate both HIV prevention and contraception without input of their partner. Condoms offer the dual purpose of HIV and pregnancy protection, but are underutilized as a prevention strategy in many parts of the developing world, where sociocultural norms can prevent women from negotiating their use with a partner. Empreva empowers women to take control of their own health and pursue a protection strategy without the input of a partner.

The team hopes to continue their success with Empreva: right now, they’re preparing to pitch the technology in this spring’s UW Foster School of Business Business Plan Competition.

We recently caught up with Renuka to learn more about the project team and research behind Empreva, as well as the team’s progress developing the product. Renuka told us how HIV and pregnancy are affecting global health, and how a technology like Empreva may improve women’s health around the world.

How did you get involved in this project?

Empreva is a direct outcome of our individual research projects in Dr. Kim Woodrow’s laboratory. Anna and Yonghou engineer MPT (multipurpose prevention) nanofibers fibers and work on in vitro validation of the product. I investigate in vivo vaginal drug delivery and reproductive immunology. My involvement in the UW Foster School of Business’ Technology Entrepreneurship Certificate program encouraged us as a team to explore the business potential of Empreva.

What got you interested in this research problem?

HIV and unintended pregnancy are serious global health challenges affecting women worldwide. With no HIV vaccine available today, prevention is key to curbing the spread of the HIV pandemic. Moreover, in regions of high HIV-incidence up to 1 in 2 pregnancies may be unintended. In addition to their impact on global health, HIV and unintended pregnancy result in significantly increased health care costs, especially in developing countries. To meet this need, we were interested in exploring new dosage forms of anti-HIV drugs and hormonal contraceptives that would equip women with an “on-demand,” easy-to-use, affordable and highly effective product that prevents HIV and pregnancy.

No woman-initiated MPT (multi-purpose prevention technology) exists yet on the market. What’s your take on why?

This is a complicated question. It’s possible that there was not previously a focus on this because doctors and scientists assumed that because condoms exist, they would be used as intended and would prevent both pregnancy and spread of infections. However, the truth is that sexual gender imbalance within different cultures around the world limits the ability of women to negotiate condom use with their partners. The magnitude of this imbalance has become evident with the spread of the HIV epidemic globe and the fact that infection is generally more prevalent in women than men.

Although it’s easy to recognize the need for a woman-initiated MPT like Empreva, it takes a long time to develop such a product. The research and development process can potentially last for 15 years or more.

Can you comment on the sociocultural norms, or other factors, that make HIV prevention difficult in the developing world, and have contributed to the surge of infection rates in young women?

There are a number of sociocultural factors that make HIV prevention a challenge in the developing world. The inability of women to negotiate condom use, and the cultural norm of infidelity in some places, definitely play a role. People in the developing role often lack of access to testing, or are tested infrequently, so they may not know if they are HIV positive. In many places, there is a general misunderstanding about HIV and how it’s spread, and many people underestimate their own risk of HIV. However, these problems are not necessarily only true in the developing world and are definitely location dependent.

Are there any sociocultural issues that might make success of a product like Empreva challenging?

One potential issue is identifying the kind of product women actually prefer to use. Growing evidence from the Gates Foundation and other research organizations suggests that women’s preferences vary across communities and countries. For example, women in South Africa may prefer to use long-term protection, like an injectable, while women in Nigeria may prefer to use a fast-acting product, like a gel. Currently, it seems like the field as a whole assumes that developing and offering a wide breadth of products, including fibers, gels, films and injectables, will have the best outcomes for prevention.

Have you encountered any research or product design challenges? How did you overcome them?

As with any research team focused on product development, we’re always working on overcoming obstacles. One of the most important issues that we’ve made progress on but are still addressing is the correct thickness for the fibers. If the fibers are too thick, they won’t dissolve quickly and will take a long time to release the drug. If they’re too thin, they start to dissolve in your hand and can be impossible to insert. We’ve optimized the fibers by investigating different polymers and fabric thicknesses, but there’s still room for improvement.

What’s next in the research and product design process?

There are a number of aspects of the research and product design process that are proceeding in parallel, which include testing the fibers in vitro and in tissue, figuring out what we can actually make on a large scale, as well as user perception testing with study groups of women to make sure that the final product is something women will actually use. These are obviously all important aspects, and outcomes from each can affect how we proceed in the overall process.

When might we see Empreva or similar products on the market? How much would they cost and where could someone buy them?

MPT innovation around new dosage forms is a major research thrust in our field. While Empreva is distinct from other dosage forms that are being developed, similar products addressing HIV and pregnancy are in pre-clinical and clinical trials. If successful, these products may be available on the market in 5-7 years. The cost of these products correlates to the cost of materials, drugs, and manufacturing each unique product. Since HIV antiretrovirals and hormonal contraceptives are still prescribed drugs, it is likely that a potential buyer would need to work through their physician to obtain these products.

Tell us about your product team.

Going into the Lifetime Innovator Award Ceremony and the STS competition, our team was comprised of me, Anna and Yonghou. Following our success at both events, three MBA students have joined our team – including a dual JD/MBA candidate. Together, our strengths as a team include research and engineering expertise as well as the business acumen needed to understand the technical and business challenges Empreva will face.

How has UW Bioengineering prepared you to succeed in confronting this research problem, and developing such an innovative product?

UW Bioengineering provides a great environment for our team to develop our technical research skills. In addition, our faculty mentor, Dr. Kim Woodrow, and UW Bioengineering fosters research translation and commercialization in the context of real-world applications. Moving forward into the UW Business Plan Competition, we are excited to continue developing the business strategies needed to bring Empreva to market.