Second-year Ph.D. student Nuttada Panpradist is confronting the world’s largest public health problems. Working with Assistant Professor Barry Lutz, Nuttada develops diagnostic tests for diseases such as HIV and tuberculosis and hopes to increase access to affordable, accessible and sustainable tools that address urgent global health needs.

Nuttada is determined to become a leader in bioengineering, an advocate for equal access to health care and a role model for women. Unable to get hired as a woman in the male-dominated field of engineering in her home country of Thailand, she decided to change direction, move to the U.S. and attend UW. Nuttada’s initial challenges as an international student only strengthened her passion and drive for bioengineering, which earned her a place in the Lutz lab. Quickly, Nuttada was leading the lab’s projects and contributing to the bioengineering research community.

So far, Nuttada’s efforts have resulted in an R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), seed grant funding and her nomination for a prestigious Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) International Student Research Fellowship. “She demonstrates a rare combination of sophisticated vision, innovation, scientific rigor, focused productivity and a knack for engaging an audience,” says her principal investogator, Dr. Lutz. “Nuttada is simply a star.”

Nuttada recognizes bioengineering as the key to global health care equality

Nuttada began her education in Thailand, where she earned a bachelor’s of engineering in petrochemical and polymeric materials. “I loved chemistry,” she explains. “I liked the magic of chemistry that when you mix two things, you come up with something different. And the new thing can actually have the potential to change lives.”

As Nuttada approached graduation, however, she discovered that job descriptions for positions in her field explicitly excluded women, listing “male under the age of 35” as a requirement. Even though she graduated near the top of her class (4th out of 154 students), her ability to pursue a career in her chosen field would be limited. She decided to pursue a new career path that suited her passion for engineering, science and education.

Before graduating, Nuttada worked as a tutor at her university and gained further appreciation for teaching others. “It was rewarding to see someone who hates math, who hates chemistry, to say ‘I love it!’” she recalls. “It was an amazing feeling to watch someone grow.” After she graduated, Nuttada took a job selling alternative medicine and became interested in the health benefits of the products she sold. “It got me excited about the field of health care,” she explains.

Nuttada’s interest in health care continued to develop as she observed that her country lacked the knowledge and resources necessary to effectively diagnose and treat infectious disease. In Thailand, she explains, “you pretty much diagnose yourself when you feel sick.” In Thailand, someone who falls ill does not typically go to the doctor to figure out the cause of his or her illness. Instead, they’ll go to the pharmacy, pick up a set of antibiotics to treat their symptoms and stop taking the medicine when they feel better. However, this simplistic approach to health care can perpetuate the impact of pandemic diseases, resulting in drug resistance, significant cost and burden, and lives lost.

Nuttada realized that pursuing a Ph.D. in bioengineering would not only allow her to pursue her interest in science and teaching, but also increase access to health care at home in Thailand and around the world. She saw bioengineering as a key to ensure health care equality for all – a basic human right, she explains. “Everyone deserves minimum health care to get a better quality of life.”

Pursuing UW Bioengineering “pretty much from the day I came to the US”

UW’s strength in bioengineering and its relative proximity to Thailand and family friends in the US encouraged Nuttada to move to Seattle. She was determined to apply to UW Bioengineering’s Ph.D. program “pretty much from the day I came to the US.”

Prior to applying to BioE, Nuttada first focused on building her biology knowledge, completing certificate programs in pharmacy technology and nanotechnology. While enrolled in North Seattle Community College’s nanotechnology program, one of her instructors introduced her to BioE’s Barry Lutz, then assistant research professor in Professor Paul Yager’s research group. She began working as an intern on a project developing low-cost HIV diagnostics.

Starting out at UW, Nuttada quickly found herself immersed in research. Although she encountered a steep learning curve at first, she says the experience was a good test for her to determine whether she wanted to pursue a Ph.D. degree. Her PI’s encouragement motivated Nuttada to explore and learn the skills needed to work on the project. “I woke up every day thinking that I had something to look forward to. Every day I challenged myself to go to the next level.”

Nuttada’s drive to succeed paid off. When her internship ended, Dr. Lutz offered her a paid position to work on a new 2012 Global WACh Coulter Seed Grant. The grant’s research team, which also involved BioE’s Dr. James Lai, research assistant professor, and Dr. Lisa Frenkel, professor of pediatric infectious disease and laboratory medicine at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, was developing a low-cost testing platform for detecting drug-resistant HIV.

Expensive, high-tech methods used to screen patients for HIV and detect drug resistance in countries like the United States are out of reach for the developing world. Dr. Frenkel created a cheaper alternative screening protocol that was feasible for developing countries, but it was still too complex for places with fewer resources. The researchers proposed that they could translate Dr. Frenkel’s protocol to a simple process requiring just a paper test strip and a blood sample. They envisioned that anyone, anywhere, could take the test and get easy-to-understand results in minutes.

Nuttada served as sole technical contributor on the project, leading laboratory work to establish proof-of-principle. Her novel findings contributed to the group receiving an R01 grant from NIH, which eventually became the focus of her Ph.D. work.

The project is rapidly advancing and the team recently tested their prototype using patient samples. The prototype is promising, says Nuttada. She found that the prototype detected drug-resistant samples nearly as accurately as a laboratory-based assay in 20 minutes. The team is now progressing to implement other steps of Dr. Frenkel’s protocol into the prototype, including DNA extraction, ligation and amplification.

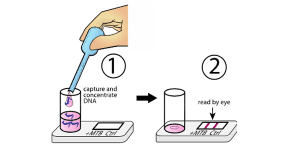

Illustration describing how diagnostic device detects TB in urine samples

Aside from her HIV assay work, Nuttada is pursuing other projects. As part of UW Bioengineering Professor Paul Yager’s larger MAD NAAT project, she led a quantitative study that analyzed how multiple types of swabs released specimen samples under various conditions. Her findings, published in September in PLOS ONE, may inform future diagnostic test research and development by helping test developers select appropriate swab types and transfer methods.

Nuttada started another project as part of a global health course she took in winter quarter 2014, GH 590, “Bioengineering Solutions to Improve the Health of Women, Adolescents and Children.” For the course’s final project, she and a classmate teamed up to propose a point-of-care diagnostic device to diagnose tuberculosis from urine samples. Nuttada and her classmate, Dr. Diana Marangu (a UW Global Health Master of Public Health student and pediatrician from Nairobi, Kenya), realized the potential of their project to impact lives. They eventually gained the support of Drs. Lutz and Lai and UW tuberculosis researcher-clinician Dr. David Horne to seek funding to continue the project. The research team recently received the 2014 Global WACh/W.H. Coulter Foundation Seed Grant to start working on a rapid, instrument-free device that can detect TB from urine samples. The researchers hope their device will offer a feasible alternative to expensive, resource-intensive methods currently used to diagnose TB.

UW’s unparalleled student experience and global impact: “It couldn’t be better than this”

As a Ph.D. student, Nuttada finds that UW provides students with remarkable resources and opportunities. “It couldn’t be better than this,” she explains. From access to state-of-the art research facilities and the ability to collaborate with world-class researchers and clinicians, to business start-up resources offered by the UW Center for Commercialization and the UW Coulter Translational Research Partnership Program, “UW gives you everything that one university can give.” Coming from Thailand, Nuttada also appreciates UW’s strength in global health research and says, “It’s a good place to expand technology to clinics in the developing world.”

From Nuttada’s perspective, UW’s culture of collaboration and focus on technology commercialization enables research projects to quickly advance from the lab to clinics, saving lives in the process. Citing her research team’s collaboration with Dr. Frenkel, Nuttada says the technology may be ready sooner than later. Due to the clinician’s involvement, the team can promptly identify and resolve problems that would affect the technology’s viability clinical environment. “We don’t want to wait,” she says. “This problem

Most important, Nuttada values UW’s support of diversity and inclusivity. She believes that UW provides each of its students an equal opportunity to impact the world. Looking back at her earlier education in Thailand, she is grateful that at UW, her contributions are valued based upon the merit of her abilities, not her gender, and that her research may one day save lives.

In BioE, Nuttada appreciates the department’s emphasis on fostering student growth. To her, the Ph.D. curriculum provides all the tools a student needs to become an independent investigator. “The curriculum is really applicable to the research,” she says, and she believes the department prepares students well for careers in both research and academia. Even though Nuttada comes to BioE from a different discipline, she finds that the BioE “accepts the broad net of knowledge from around the world,” which facilitates innovation in research and medicine.

After completing her Ph.D., Nuttada aspires to pursue a career in academia. She wants to become a professor of bioengineering, mentor the next generation of scientists and engineers, and advance universal access to healthcare around the world.

Before then, however, she looks forward to her current projects and future discoveries. She is planning to pursue a common thread between her HIV and TB projects: she recently learned that DNA markers for HIV are present in urine. She ultimately envisions combining her approach to diagnosing TB from urine with her test for HIV into a single device that would enable a clinician to test a patient for both diseases simultaneously.

An example of Nuttada’s culinary skills – a cake that won BioE’s Holiday Party 2014 Bake-Off

In addition to her independent research projects, Nuttada has mentored several undergraduate students. Outside the lab, Nuttada has served as a panel member for several STEM-related events, including a UW Global Health’s “Re-engineering Global Health” and a Bellevue School District high school STEM fair. She also participates in BioE’s outreach activities, most recently at UW Engineering Discovery Days and Innovation Day at the Bill & Melinda Gates Visitor’s Center. In her spare time, Nuttada enjoys a wide array of diverse interests including building and painting furniture, carving fruit and other food, art, decorating baked goods, sightseeing, biking and hiking.